Heavitree Local History Society

Taking an interest in Heavitree's past

Articles

Articles relating to Heavitree and its past.

These may be connected with research that has been undertaken, subjects that have been covered at our quarterly meetings, or, material that has been gleaned from other sources.

- Heavitree - An Overview

- The Origin Of 'Heavitree'

- Fore Street Heavitree - A Roman Road?

- Heavitree And The Domesday Book

- Heavitree Parish Boundary

- Wonford And The Great House

- The History Of The Ludwell Valley

- Heavitree Stone And Heavitree Quarries

- A Social History Of The Royal Devon And Exeter Hospital

- Digby - City of Exeter Lunatic Asylum - Part 1: 1890

- Heavitree And Infectious Diseases

- Heavitree As A Place Of Execution

- Higher Cemetery

- Almshouses Of Heavitree

- Pubs Of Heavitree

- The Heavitree Brewery

- Heavitree Toll Houses

- Growth And Development In The Nineteenth Century

- The Gordon Lamp

- Heavitree And The Railways

- Heavitree And The Trams

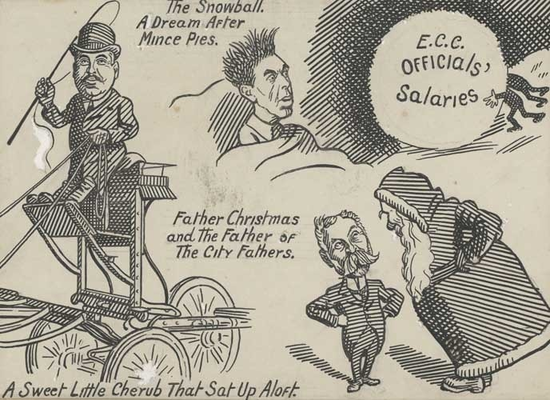

- Heavitree Urban District Council

- Heavitree Pleasure Ground

- The Widening Of North Street

- The Annexation Of Heavitree

- Churches Of Heavitree

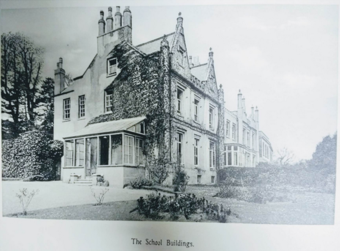

- Education In Heavitree

- Retailing In Heavitree

- Recreation And Pastimes In Heavitree

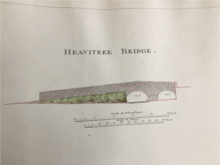

- Heavitree Bridge

- Wyvern Barracks

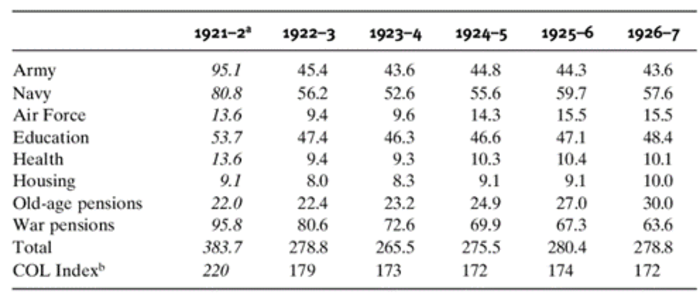

- The Inter-War Years: Homes For Heroes

- Heavitree In The Second World War

- The Post-War Years: Factory-Made Housing And Model Cities

- Heavitree Social Centre

- Famous Heavitree Residents

- Neighbourhood Watch 1831 Style

- Disorderly Houses In Heavitree

- Heavitree Postboxes

- Researching A Heavitree Silk Merchant

- Researching Heavitree At The Devon Heritage Centre

- The Cathedral Archives And Heavitree History

- Ladysmith Road Squilometre Project

- The Entrepreneurial Spirit of Heavitree And The Heritage Of Victor Street

- Mile Lane, Beacon Heath: A Hidden Heavitree Treasure

- Memories Of Heavitree

- Snippets From The Local Press

- Heavitree Around the World

- Obituaries

Heavitree - An Overview

For many centuries Heavitree's parish boundaries swept right around from Countess Wear to Cowley, although by 1800 its population, despite its size, was less than 900.

By the time the Heavitree Urban District Council (HUDC) was set up at the end of the 19th century, Wonford, Polsloe, Whipton and Stoke Hill were still within that boundary. Nowadays Heavitree is an identified ward for local election purposes - an area loosely centred on the Fore Street shops.

It is possible that Fore Street, Heavitree is on the route of a Roman road into Exeter, but to date this is unproven. What is known is that Fore Street was on the main Exeter to London road by the 1500s and this, together with the location of the parish church, led to Wonford's local pre-eminence being gradually usurped by the hamlet of Heavitree.

It is known that before William the Conqueror arrived on the scene Heavitree manor was part of the Wonford royal estate. Wonford was the name given to an ancient 'hundred' but unlike many other hundreds it didn't have a minster church. The role seems to have been taken by an early Christian place of worship on a prominent position on the edge of the estate at Heavitree.

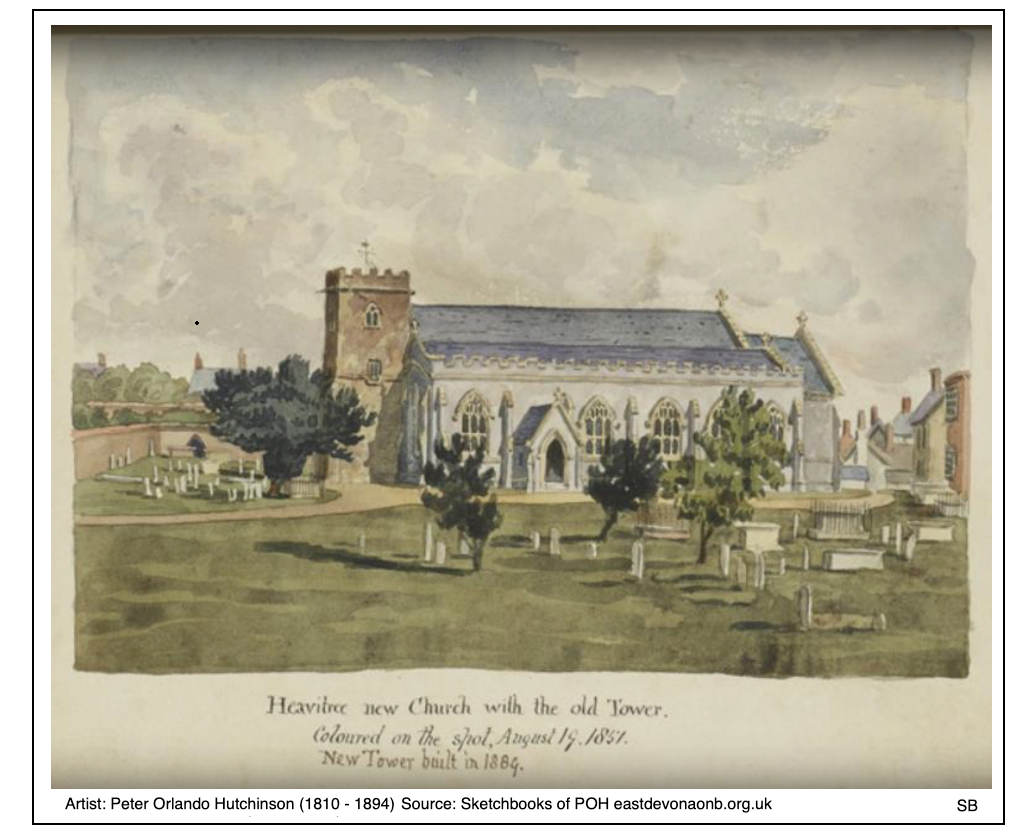

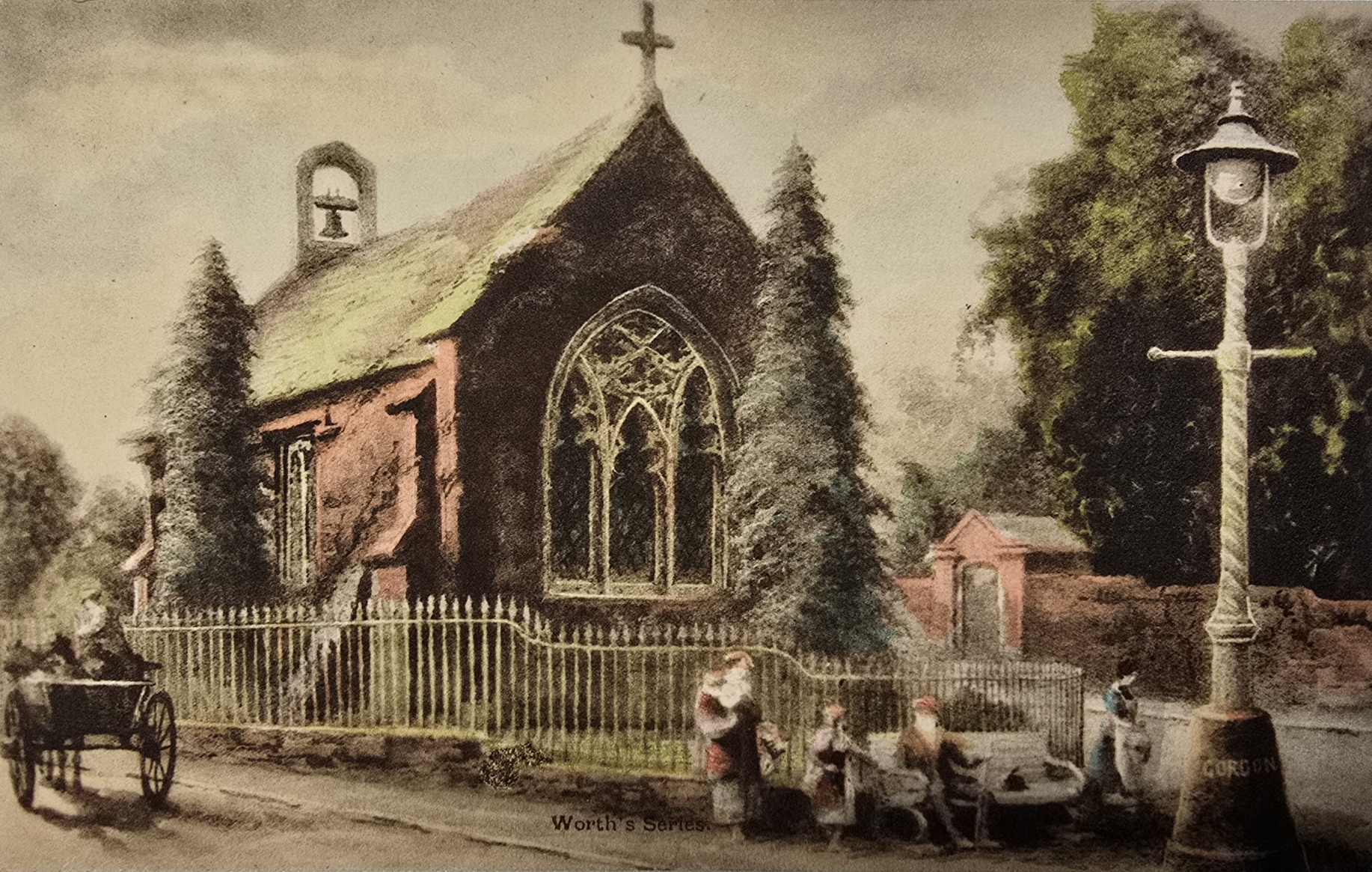

The Parish Church, Heavitree in 2013

For centuries, Heavitree provided the inhabitants of Exeter with food, building materials, and, as the city grew in importance, labour. However, the relationship between the city of Exeter and the village of Heavitree wasn't always amicable. Exeter, because of its importance, has been besieged on many occasions since 1066. The besieging armies would have camped in Heavitree and demanded that the local farmers provided them with food while stopping trade with the city's inhabitants.

Although there is no recorded evidence, it is likely that this forced collaboration would have led to recriminations when hostilities ceased. This may have been the reason why people living within the city walls called those living in St Sidwell's "Grecians", or untrustworthy, and Heavitree was nominated as the place for executions.

Despite this friction Heavitree became a honey-pot for wealthy Exeter merchants and people returning to England after making their fortunes with the East India Company. One of the main reasons for the building of Baring Crescent, Salutary Mount, Mont-le-Grand and Regents Park during the first half of the 19th century was the good health record of the parish. Whilst scores of people died from Cholera in Exeter, Heavitree residents escaped almost unscathed.

This expansion escalated as Exeter's prosperity increased. By the middle of the 19th century the city fathers were keen to include Heavitree in the city's boundaries, but it wasn't until 1913 that annexation finally took place and ended a thousand years of independence.

Scroll to top of pageThe Origin Of 'Heavitree'

Most place names are either personal, i.e. named after a person, or topographical, i.e. named after a local feature in the landscape.

These derivations are not always apparent in modern English place-names as most are rooted in ancient languages such Celtic, Latin, Old English or Norman French.

Another barrier to tracing the derivation of an English place-name is that it will undoubtedly have changed over the years. The following are just a few examples of Heavitree found in old texts and documents:

- 1086 Hevetrowa (Domesday Book)

- 1130 Hefatriwe

- 1179 Eveltrea

- 1270 Hevedtre

- 1345 Hevtre

One theory as to the origin of the name Heavitree is that it was derived from it being the common place of execution for malefactors, signifying the heavy or sorrowful tree. Another possibility is that it refers to the ‘head tree’, and yet another suggestion is that it is made up of ave or avon (water), and tree the British word for town or settlement.

Most place-name experts now agree however that it probably derives from the personal name Hefa and the Old English word treow meaning a tree, post or beam. Heavitree is included in a group of 38 settlements which have similar characteristics, namely adjacent to a boundary of an estate and associated with a meeting-place. A tree is a natural marker for both purposes.

Scroll to top of pageFore Street Heavitree - A Roman Road?

Introduction

There has been much speculation and debate over the possibility of Fore Street Heavitree having a Roman origin but it may never be proven. Even if it began its life as a solidly-built Roman military road, nineteen centuries of continuous use, and its slope, would have removed all physical evidence. However, it is a worthwhile exercise to investigate the possibility by association with the proven routes and the intelligent interpretation of the topography where gaps exist.

Roman Technique

Roman roads were constructed by the army, for the army. When the Second Augustan Legion built their fortress at Exeter in the 50s A.D., roads leading to it from the rest of Roman Britain, and in particular the contemporary Legionary fortress at Lincoln at the other end of the Fosse Way, will have been laid out in predictable ways, with forts placed at intervals equivalent to a day's march. The Antonine Itinerary of the third century A.D. listed the mileage between important places such as posting stations and major towns. Included on the south coast route between Dorchester and Exeter, for example, is Moridunum, which may mean defensible place by the sea, and, although no hard evidence for a fort has yet been found, it is likely to have been close to present day Seaton. To the west of Exeter there is Nemetostatio and may be the fort known as North Tawton. Further west we have Tamaris, yet to be found, but must be a fort guarding the crossing of the river Tamar. It took until 1998 to find the Roman fort near Honiton on the Fosse way; everyone knew it was there somewhere.

Physical Evidence

With the aid of an Urban Database, which precisely locates and superimposes all known archaeological evidence onto modern topographical maps, it is now much easier to see what was going on at any given period. The gates and many of the roads leading from the original Legionary fortress are known from excavations. An aerial photograph showing the very straight line of Topsham Road would have continued through Exeter's South Gate into the fort and out of the North Gate. Interestingly, the suspected route from the North Gate was never found during excavations in the area of the Iron Bridge. However, evidence has been found for the road turning north and running up what is now Paul Street. An East Gate, near St Stephen's Church in the High Street, would have run in a straight line to join what is now Sidwell Street. The apparent wobble in the line of this road, from the later City Gate to Sidwell Street is thought to be the result of recutting City defences during the Civil War. The road from the West Gate would have run to the Exe Bridge and beyond.

Thus far none of this helps the cause of Fore Street Heavitree except that during recent excavations in Princesshay, Roman road metalling was unexpectedly found running diagonally, due East from the Fort. This is still not quite in line with Fore Street Heavitree but does allow us to break the predictable 'dead-straight' grid mould.

Interpretation

Of the two Roman roads running to Exeter from the east - the Honiton-Exeter route seen as an extension of the Fosse Way, and the south coast road from Dorchester - the best alignment for Fore Street Heavitree comes from the latter. The south coast route arrives at Clyst St Mary and the bridging of the Clyst, then follows a straight line section of the Topsham parish boundary (always a good indicator of pre-Norman land division) to Sandy Gate, then on to Quarry Lane and East Wonford Hill. The building of the railway, outer bypass and M5 motorway now make this route less obvious.

The Fosse Way from Honiton is known with certainty as far as the Rockbeare Straight. Margary describes a subsequently bendy route from Clyst Honiton, closely following the low ground of the old A30, to join the South Coast road at Heavitree Bridge at the bottom of East Wonford Hill (Margary, 108). However, if one takes a look at a modern map we see another potential route into Exeter over a ridge via Blackhorse Lane to Gipsy Hill and then Hollow Lane. From this point the line can be imagined running to join the Pinhoe Road close to Polsloe Bridge, then to Blackboy Road, Sidwell Street and Exeter's East Gate. Unfortunately no Roman road was discovered during the building of the M5 motorway.

Conclusion

There seems to be little doubt that Fore Street Heavitree had its origins as a Roman road and could have led to both the East Gate and the South Gate of Exeter, forking at Livery Dole, before running via both Magdalen Road and via Heavitree Road + Paris Street.

References:

Margary, RD, 1955 - Roman Roads in Britain Vol. 1, London

Heavitree And The Domesday Book

The Domesday Book is not consistent in the manner of its recording; Heavitree's entry is very short on detail. It mentions only two carucates of land and two ploughs: one for Roger, who holds the manor, and one for the villain - the two serfs were probably ploughmen. That makes for a population of just four families in 1086: Roger's, the villain's and the two serfs' - surely there must have been more.

A carucate, like the hide elsewhere in the country, is a measure of cultivated land which a plough team could work in a year, and could be used to calculate tax. For most of the country, a carucate, or hide, would have been reckoned on 120 acres but in the southwestern counties (heavier soils?) it is more often reckoned at only 40 or 48 acres (Finn, 25).

How much bigger than its likely 96 acres of arable was the manor at this time? What about woodland (crucial for fuel and the grazing of pigs), orchards, pasture, sheep and cattle? How did this tiny manor, and its later church of St Michael, in the two centuries following Domesday Book, become the centre of such a large parish, stretching from Cowley Bridge in the north to the Clyst at Bishops Clyst in the south, including a total of ten churches and chapels (Orme, 121)?

A map showing the extent of Heavitree parish

at the end of the 13th century (Orme, 1991)

As for the plough and its oxen team, it must be remembered that ploughing had been developed over thousands of years before 1086. The plough itself was a valuable and effective tool, with all the components we see on a modern plough: a coulter to cut the turf, an iron 'share' to break the ground, and a mouldboard for turning the furrow. Ploughshares were even sought as payment for rents (Finn, 57). The oxen (castrated bulls), were small beasts about the size of the Dexter breed, and the eight would constitute two teams of four.

References:

Finn, RW, 1973 - Domesday Book; a Guide, London;

Orme, NI, 1991 - The Medieval Chapels of Heavitree, Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological Society No 49, 121-129

Heavitree Parish Boundary

For at least 1000 years prior to 1913, when it was annexed by Exeter, Heavitree parish, which included Polsloe, Stoke Hill, Whipton, Broadfields and Wonford, looked after its own affairs. It has been suggested that the site of its parish church, St Michael and All Angels, was one of the earliest Christian sites in Devon.

The administrative area known as a parish appears in King Alfred's laws and had both spiritual and secular functions. As land-owners and residents had to pay a tithe or tax to their parish church it was essential that the vicar and church officials knew the precise extent of their parish. The parish gradually became the accepted local government unit below the county and was given responsibility for administering the poor law acts, highway maintenance and enforcing the law.

The need to define and defend individual and group territorial boundaries seems to be a basic human instinct that is also found in many animals. The practice of marking land boundaries with physical objects such as wooden posts or stones has lasted for at least 3000 years (see Deuteronomy 19:14) and Tudor boundary stones marking Heavitree's parish boundaries can still be seen.

A map from the 1930s showing Heavitree parish boundary

Boundary stones or markers rarely defined every bend and kink in parish boundaries and as accurate maps only became available in the late 19th century parish councils used a technique to define and identify boundaries which dated back to ancient Greece and the Romans. It went under the name of 'beating the bounds'.

Throughout the country vicars and parish officials led a group of their parishioners, including in many places young boys, around their parish boundary. Each boundary stone or significant bend in the boundary was struck with a willow wand or a rock. In many parishes a boy was raised by the ankles and his head was bounced on the stone or the ground. The reasoning was that making young boys witness and take part in in the ceremony would ensure the survival of the group memory and they would make convincing witnesses if the boundary dispute was ever brought to court.

Perambulating Heavitree's twenty mile boundary took most of a day and regular stops for refreshment were required. On returning to the church an ale-feast was often held. Many parishioners used the occasion as an excuse to get drunk and misbehave. It is perhaps no coincidence that the word 'bounder' means a cad or person of objectionable manners.

Heavitree parish boundary overlain on a modern OS map

The beating of the bounds traditionally took place on Rogation Sunday, but in an attempt to avoid the fights that often broke out when groups of high-spirited, semi-intoxicated youths from neighbouring parishes met, some churches switched the ceremony to their church's dedication day.

Some of the stones which marked the boundary of Heavitree parish have been in existence for many centuries, but in 1897 the Heavitree Urban District Council celebrated Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee by erecting some additional stones and reviving the beating the bounds ceremony which had lapsed over the years. The ceremony again lapsed after the 1913 annexation, but was revived for a second time in 1975 by a group of local enthusiasts. Since then the ceremony has taken place every three years or so.

A booklet published in 2007 by the HLHS exists containing a record of Heavitree's surviving parish and the UDC boundary stones + a description of how to follow as closely as possible the 1897 boundary.

Anyone wishing to attempt the walk will find a good street map is useful. Walkers are warned that bridle paths are often very muddy in winter so stout shoes are advisable; flooding is also possible in low-lying areas after prolonged heavy rain. The Countryside Code should be adhered to at all times. The walk is of moderate difficulty with one long climb in the Stoke Hill area.

Boundary Walk - Full route (14.3 miles, 9 boundary stones)

Boundary Walk - Shortened route (0.3 miles, 4 boundary stones)

Wonford And The Great House

Numbering in this article corresponds to that in the Wonford Village History Trail, designed by the Heavitree Squilometre.

This is a great little walk that takes you through the history of the area. Using wi-fi, it can be followed as you go from the browser on your mobile phone.

Further information:

Wonford village was part of the historic royal manor of Wonford, and was named after the old name for the Northbrook: Wynford.

There is a direct line along Wonford Street: from the site of the Manor House at one end to Heavitree Parish Church on higher ground at the other.

Church and Manor were there as prominent landmarks. This is indicative of the power relationship in the 12th century: the serfs / people would be living between two powers, one at each end of the village: church and lord.

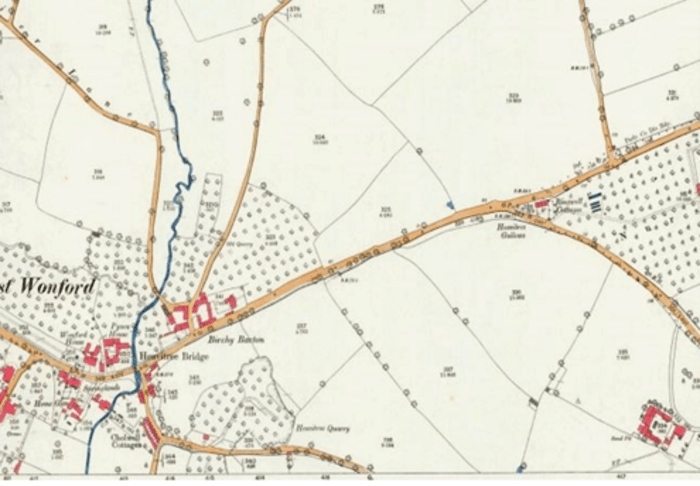

Early 20th century map of Wonford Village (left)

Yeomen would have rented burgage plots from the lord, thus he would have held that village. Back-alleys like Hope Lane and Bovemoors indicate that the village is likely to have been planned this way, as statement of ‘you belong to me’!

The 1901 OS map of the area shows remnants of medieval settlements and three main centres of population: Wonford village, the quarries, and the centre of Heavitree.

In the past, Heavitree was the outlier of Wonford, and would have gradually grown. These days, Wonford is considered to be the outlier of Heavitree.

1. Wonford Great House

The Great House would have faced the village. Looking at Coronation Road, one can almost see the shape of where it would have been. A care-home now stands on the site.

A lot of heritage was lost as developers moved quickly giving archaeologists insufficient time to investigate what might have been left there. However, early pottery from the Great House has been discovered, dating from the late 1100s / early 1200s, the time of King John.

It's believed that the DeMandeville’s owned the House, although it's unlikely that they lived there. By 1236, it seems to have gone to the Gervaise family: Walter and Nicholas. These would have been French / Norman noble families.

Research has concluded that the House:

- Sat on a square plot of around 700m2, including a square moat

- Its front gate would have faced the village, with a small bridge over the moat

- It would have had a steeply gabled roof and small windows

- The first house, dating to around 1200AD, may have been timber.

Later versions were almost certainly constructed from Heavitree Stone

Local artist, Steve Bramble, helped design a logo based on these facts. This can be seen on an information board where the House once stood.

Information board giving details of Wonford Great House

2. South Wonford Infants’ School

A typical example of a Victorian school. The building dates from 1878, and originally educated around 60 children aged 4-7. A year later an additional classroom and chapel was added.

Almost every house in Wonford Street had children who attended the school.

It ceased to be used for teaching in the 1940s, and is now flats.

South Wonford Infants’ School

3. Site Of Smith’s Dairy (St Loye's Court)

Where St Loye’s Court now stands, there was a dairy in the 1900s.

Charlie Smith and his son Tom had a dairy farm at the top of Quarry Lane; they sold and delivered milk by horse and cart from this site.

Apparently, Charlie used to sometimes drink too much cider, but his horse knew the way around.

4. South Wonford Terrace

A terrace of working-class houses, built in the 1840s to house gardeners and labourers.

As Wonford Village became less reliant on local farms and orchards from the 1900s onwards, the houses became homes to dressmakers, nurses and cab drivers.

Originally built as two-up two-down cottages, the number of occupants ranged from 1-8, as people would often rent out a room to supplement their income. For example, the Sinclair family of 6 also had 2 lodgers.

5. Scudders Buildings

A row of workers’ cottages, originally thatched, built in the 1860s.

They were home to railway workers, carpenters, labourers and bricklayers. William Gibbs, a labourer for the council, lived at number 61 in 1911 with his 8 children and wife, all in one tiny cottage.

Well-known character Granny Lake lived at number 63, and would sit outside making Honiton Lace.

There were two toilets outside for the whole block. These were eventually moved inside due to the risk of Scarlet Fever, but the house dwellers were reluctant.

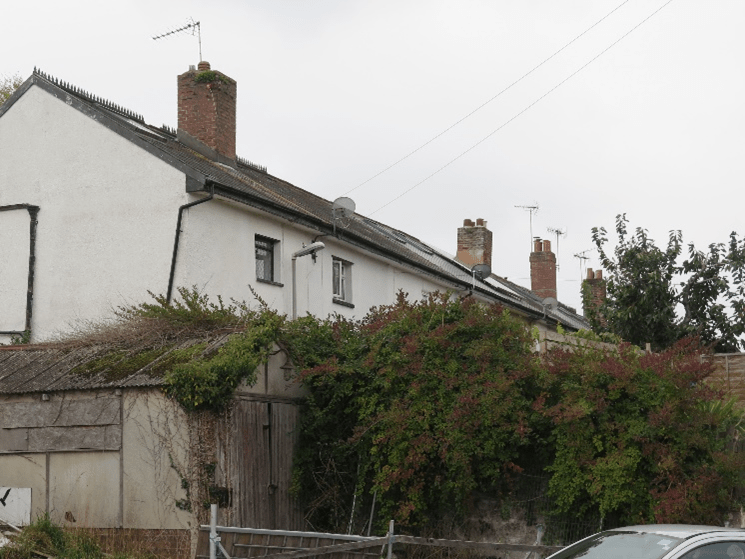

Scudders Buildings

6. 45 + 47 Wonford Street

Two red brick buildings, built in the 1850s.

Number 45 is named 'Verney House'.

Number 47 was originally a shop. A quick look at its occupation over the years shows it being a coal merchant, hairdressers, TV repair shop, video rental shop and gas appliance shop. It was converted into flats in the 2000s.

There is water running underneath the road surface here. This could well be the culverted Blackbrook water course, which once ran through the village, and likely filled the moat of the Great House.

7. Vine Cottage

Probably the oldest building on the street. It was built before 1800, with recent changes visible.

In 1834, a robbery occurred in which £30 was stolen from William Barrell, whilst he and his family were at church.

Subsequently, the family must have fallen on hard times as William was sent to debtors’ prison in 1845. He committed suicide by jumping into the River Exe in 1852.

In 1861 John Madge, a licenced victualler, bought the cottage.

Vine Cottage

8. 31-35 Wonford Street

Evidence of the Exeter Blitz. A bomb killed two here, and left a crater 43 feet in diameter and 15 feet deep.

9. Cherry Gardens

A small development of houses from the 1960s, built originally for staff and families of the prison service.

It was built on the cherry orchard run by the Langdon family, who also had a butcher’s on Woodwater Lane.

The orchards were used for a locally-made cherry brandy. The Heavitree Brewery later owned it and claimed it was the best you could buy.

10. The Wonford Inn

Previously a private house known as Oakbeer Cottage, part of a farm.

It became a pub in 1866. It is the last of three pubs serving Wonford Village, and looks set to close.

The Wonford Inn

11. 3-15 Wonford Street

Dating from the 1830s, the first building (number 3) was originally a shop that sold beer. In those days, tea and coffee were extremely expensive, so beer was widely drunk instead.

In the 1950s, the shop was called Rosie's, but was renamed Elston's when Rosie married a Mr Elston.

12. Hope Hall + Hope Place

Hope Hall was built as a Baptist Chapel in 1905. The Baptists used the building until 1931 before vacating to larger premises a short distance along Wonford Street.

The building has had various uses over the years, and for a while was Heavitree’s Community Centre. When it was decorated, the baptismal font was found under the floor.

Next to the Hall are eight terraced cottages built in 1890. They shared a common water pump and probably privy, as was the norm at that time.

Hope Hall And Hope Place

13. Fort Villa

In the 1800s, as Wonford Village expanded, a number of larger houses were built alongside the workers’ cottages.

Built in 1826, Fort Villa is one of these. An example of a grand villa that would’ve been occupied by ‘the gentry’.

Alfred Brooking lived here between 1897 and 1926; he was chairman of Heavitree Urban District Council. When he died, he left the request that he be buried with an open bottle of chloroform.

Fort Villa was converted into a residential home for the elderly in the 1960s, reputedly Exeter’s first.

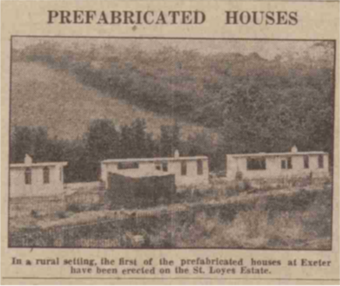

14. Cornish Units

During World War II, many homes were destroyed and people were left with nowhere to live.

Pre-fabricated houses, known as Prefabs for short, were a short-term answer to the housing crisis.

Prefabs could be built in a matter of hours from concrete sections, manufactured in the factory and transported to the construction site. Often, the entire structure was transported from A to B on the back of a lorry.

There were a number of designs of prefab. The Central Cornwall and Artificial Stone Company constructed thousands of one of the most easily-recognisable types.

Prefabs were built to be temporary and only last 10 years, but many still stand, such as those in Butts Road, built in the 1950s.

15. Murder / Suicide

On a February morning in 1933, neighbours heard gunshots coming from a cottage.

A woman was found with one foot protruding from a downstairs window; it seems she was trying to escape. She had a severe gunshot wound to the back, and died on the way to hospital.

Her husband was found inside with his head partially blown away. He was holding a double-barrelled shotgun with a cord attached to the trigger.

16. Baptist Chapel

Opposite the Wonford Inn, stands the “new” Baptist Chapel, built in 1931 as a replacement for Hope Hall.

The Chapel closed in 2003, as the congregation had fallen to just two. A reflection of just how markedly allegiance to God, and thus church attendence, has nationally declined since the end of World War II.

In 2004 the premises reopened as the Baptist Union headquarters.

Baptist Chapel

17. Wonford Garage

An ‘old school’ garage stands on the site of what used to be Shepherd’s Court, a terrace of workers’ cottages.

In 1956, the business was owned and run by JK Pritchard and Sons. To this day it is run by the Pritchard family.

18. Site Of Abott's Farm (Draycott Close)

There used to be four acres of orchards here, as well as a fine thatched farmhouse.

The house was demolished in 1964 to make way for Draycott Close.

19. Heavitree & Wonford United Services Victory Hall

Built in 1922, by local veterans who served in World War I, as way to remember fallen servicemen, and as a meeting place for the local community.

Heavitree & Wonford United Services Victory Hall

20. Site of Havill’s Farm (Amersham Court)

On this site in 1840, sat “a commodious dwelling house” called 'Havill's Farm'.

Herein lived George Havill with his wife, Jane, their ten children, two servants, and a nursemaid. As well as the main farmhouse, gardens and orchard, George Havill owned Havills Meadow (roughly where the Wonford Leisure Centre now stands).

A Master Butcher by trade, he continued to build his business in the 1870s and 1880s with the help of sons Albert and Frederick (who also became butchers), as well as a number of live-in Butchers Apprentices or Assistants.

Alongside the farm, was Havill's Slaughterhouse, one of two in Wonford. There you could buy fresh eggs, milk and cream. The freshly slaughtered meat was sold at Havill & Sons butcher's shop in Exeter.

Scroll to top of pageThe History Of The Ludwell Valley

Pre-History

Ludwell Valley is a place people have been drawn to since the Neolithic period. It has been continually used and occupied for 6,000 or 7,000 years. There is nowhere else in Devon that can say this.

People used flint and other stones to make tools e.g. blades and scrapers. From the Iron Age onwards, the clay was used for pottery, and the land for agriculture. A lot of early pottery found on sites elsewhere in Devon has been shown to have been made from clay from Ludwell Valley. There is no evidence of kilns in the Valley, which suggests that the clay may have been dug up, then made into pottery elsewhere.

An aerial view of the Ludwell Valley

There are long gaps in the historical record, the next detailed glimpse we get into the history of the Valley being in the 1840s. However, there have been a number of finds, a selection of which can be seen in the RAMM ‘Making History’ section:

- Several enclosures and barrows, likely to date back to the Bronze Age;

- A medieval field boundary buried on the northern edge of the Valley;

- The Topsham/Heavitree parish boundary going back to at least the tenth century;

- A large number of bones unearthed in the 1960s in a field below Pynes Hill, which may be remains of those who died in the Prayer Book Rebellion battle of Clyst Heath on the 4th and 5th August 1549;

- Seventeenth century pottery fragments: Westerwald pottery, which came from Germany and was owned by high status individuals; and courseware, made locally, possibly from Ludwell Valley clay, and used by lower status people.

Why Is It Called Ludwell?

“Ludwell” comes from two Old English words: “hlude", loud, with "hlaw", a hill; and hence "the loud (or rapid) river by the hill”?

W.G. Hoskins suggested the name means “loud spring”. There is a spring, now under the kitchen floor of Ludwell House. Maybe there was an old watercourse, fed by the spring, which Ludwell Lane now follows, flowing down to join the Northbrook?

“Hlaw” translates not only as hill but also mound, especially a barrow. Was there a prehistoric burial mound, the haunt of restless unquiet spirits of the ancestors?

How The Northbrook Gave Wonford Its Name

The old name for the Northbrook, recorded in a Saxon charter of 937 AD, was Wynford. This probably derives from the Celtic “gwyn ffrwd”, meaning the white, fair, or holy stream.

“Wynford” changed over time to “Wonford” and this became the name of the manor of Wonford, which belonged to the Saxon kings, and thence of the Hundred.

Heavitree, built on the Exeter to London road, gradually became more important. Wonford had ceased to be a royal manor by the 12th century; Heavitree is the name the parish has been known by ever since. We can see from maps that almost all Ludwell was originally within Heavitree Parish, with only a tiny bit in the Topsham Parish.

Ludwell Lane

The footpath running up from Ludwell Lane by the side of the Fernleigh Nurseries rejoins Ludwell Lane and aligns precisely on Heavitree Parish Church. Did it originally run straight to the church, and the modern alignment is to avoid the steep slopes?

The northern end of Ludwell Lane disappears under Rydon Lane. This is where one of the two main local Iron Age encampments was! Could Ludwell Lane have followed a route used by our Iron Age ancestors over 2,000 years ago to travel between one of their main settlements and the sacred site marked by the ancient yew tree which may have given its name to Heavitree?

The 1844 Tithe Map

In the early 1840s, a tithe map was drawn up for each parish. The purpose was to assess who owed tax and how much. Most of the tax was due to the vicar or parson, replacing the old system whereby farmers and smallholders had to give one tenth (a tithe) of their produce to the vicar every year. The map records the name of every field, its size, whether it was arable or pasture, who owned it and who farmed it.

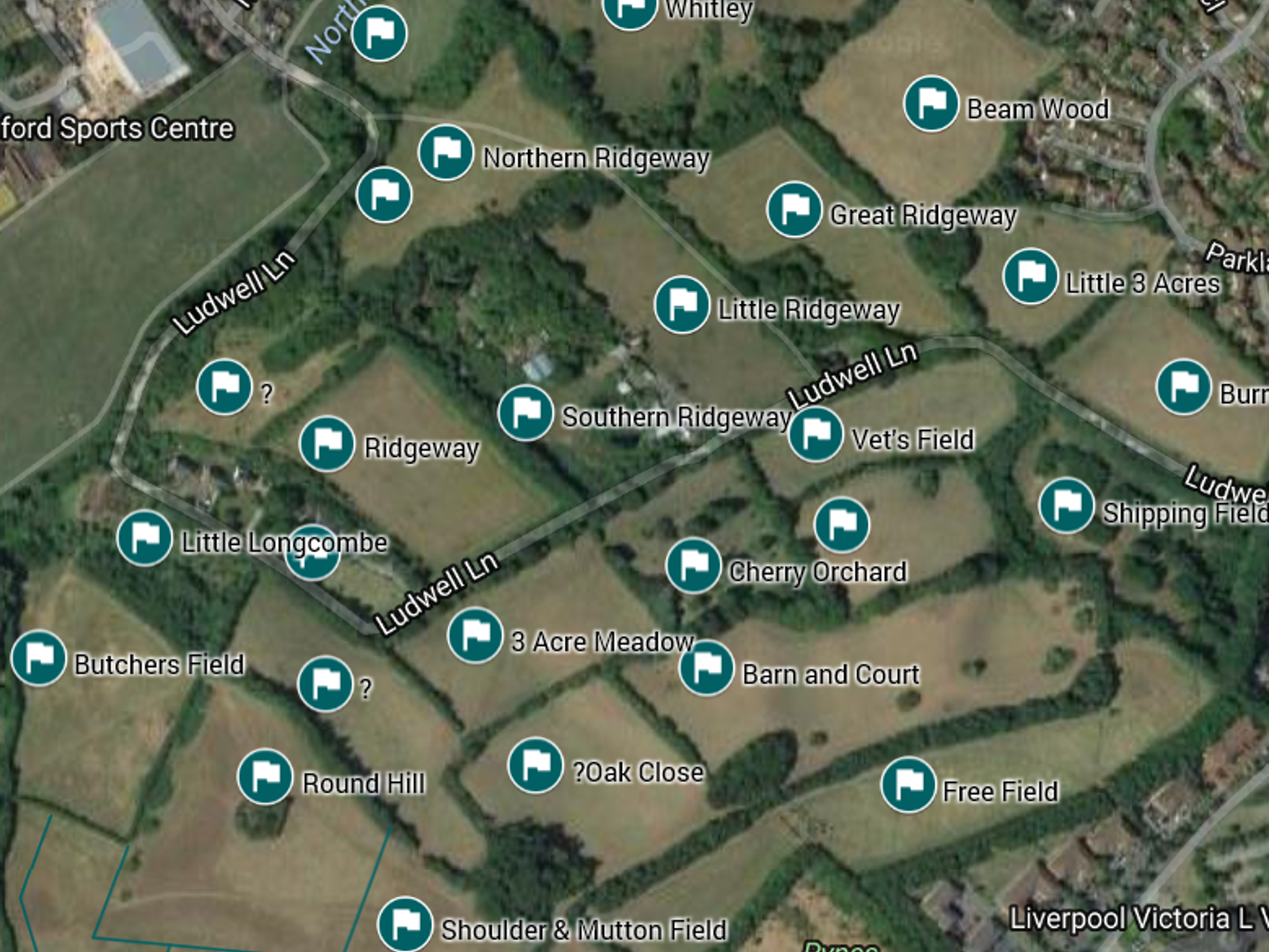

An aerial view of the Ludwell Valley showing the 1844 field names

Ludwell Valley was within Heavitree parish. The vicar was owed £450 a year; other lessees another £580. It would take a craftsman about 8 years to earn £450 in the 1840s!

Fields were fairly small, typically 4 or 5 acres. Unlike today, most were used for arable crops, with lots of fruit. Most landowners were men holding a fairly small number of fields, although a few owned larger holdings, up to 50 fields and over 200 acres. Fields were not necessarily grouped together into blocks according to ownership – it was more common to own ‘one here, and one there’.

Rev. William Arundell

The Rev. William Arundell was born in 1798 in Pinhoe. He was 46 when the Tithe Map was drawn up, and owned nine fields in the Valley, plus another sixteen elsewhere in the parish. By the time of the 1861 census, if not before, he was the rector of Cheriton Fitzpaine, which is about 5 miles north of Crediton. He was then 63, his wife, Sarah, only 37. Sarah in fact was his second wife, whom he married in 1847. They had at least two children, sons aged 11 and 12, although they were not living at home (maybe away at boarding school?). The family were pretty well off, having no less than seven live-in servants: a footman, a groom, garden boy, cook, kitchen maid and two housemaids. By 1871, times must have become a little harder and they had only four servants. The two boys had both gone up to Oxford University. Two years later, William died, aged 75, leaving nearly £12,000 (equivalent to over £600,000 today).

Samuel Melhuish

Samuel Melhuish, the Rev. Arundell’s tenant farmer, lived in the Abbots and Pyne area of South Wonford. He was born in 1781 in Cheriton (thus the connection to his landlord?), so was over 60 at the time the tithe maps were drawn up. His wife was called Ann, and at the time of the 1841 census, there were three teenagers living with them, a girl of 18 and two boys, aged 14 and 17, both agricultural labourers. By 1851, aged 70, he was farming and employing two labourers, William Clement and Arthur Barnicoot, both of whom lived with the family. His 9 year old grandson Robert was also living with them as was a female house servant called Ruth Eveleigh. By 1861, things had changed again. Samuel was widowed, but still head of the household, still farming at the age of 79, employing three men and a boy. Living with him was his 47 year old son Robert, also a farmer, Robert’s wife Martha, Samuel’s grandson and three grand-daughters, the younger two of whom, aged 10 and 14, were at school. This arrangement continued until 1871, although by then the family included Samuel’s one year old great grandson, William, and a 16 year old agricultural labourer called William Philips. Samuel died later that year at the very good age of 89. The family lived at Pynes Farm.

Pynes Hill Farm

The farm was on the opposite side of Ludwell Lane to the Fernleigh Nurseries in the corner of what is now the Cherry Orchard. It had been there since at least the 1890s, and probably a lot longer, but was gone by the 1960s, and possibly by the 1940s; there are still signs if you look carefully enough. The gateposts of the entrance to the Cherry Orchard from Ludwell Lane are solid stone affairs, very different to the more modern gateposts used elsewhere in the park by the Council. They are in fact the gateposts of the old farm entrance. Near the cattle’s drinking trough you can find the odd brick or fragment of floor, all that is left of that farm.

A map showing the location of Pynes Hill Farm

Francis Hurford of Topsham leased part of this farm to Mark White of Hallhayes Farm, Wellington, Somerset in 1932. The lease had strict conditions: not to break up any permanent pasture; to preserve all the trees in the Cherry Orchard; maintain the hedges in good condition; keep at least 40 apple trees and currant bushes in the garden; manage the farm “according to the best rules of husbandry practiced in the neighbourhood”; prevent, as far as possible, any trespass onto the land; and purchase the farm’s milk round after a year.

The Snow Family

The Snow family were connected with the Ludwell Valley in the early 20th century. Edgar and Hilda Snow were landlords of the old Country House Inn on Topsham Road (and their family landlords of two other Heavitree Brewery pubs: The Windsor Castle and the London & South Western Tavern). They did well there, and in 1920 bought Ridgeway field, and then Ludwell Gardens in 1928. This was productive arable land – they grew fruits and vegetables, and it was also good for bulb growing. They developed a commercial business – sending daffodils and other flowers to Covent Garden market in London, with, it is said, flowers even being exported to Holland! Tulips to Amsterdam! The family only sold these fields to the Council in 2019.

Edward Snow and his family, outside the Country House Inn, Topsham Road

(image courtesy of Mrs P & Dr G Richardson)

Edward Snow and his family, with cut flowers grown in the Ludwell Valley

(image courtesy of Mrs P & Dr G Richardson)

The Council And Ludwell

In the 1920s, the council started buying up land around Exeter, first to re-house people from the old West Quarter and then after the war, to replace houses destroyed by enemy bombing. Most of the land is now the Rifford Road and the Burnthouse Lane estates. Ludwell Valley was spared, presumably because the land was too steep, and Wonford Playing Fields because the land had been used as a tip, and then for dumping some of the rubble from the wartime bomb damage.

Once the Council took over ownership of fields in the park, they installed tenant farmers. The last tenant was Bernard “Tiger” Hooper. He was said to be a strong-willed man. He grazed his cattle on the park all year round, which made it a muddy and smelly experience for walkers, although some field edges were fenced off for them. He had a piggery where the new cherry orchard has been planted; full of old railway carriages, gates and vicious dogs! When Tiger died in 1998, the Council decided to take back the management of the land in order to have better control.

In 1983, the Council took the far-sighted decision to set up Valley Parks in Exeter, so Ludwell is protected. In May 2019, the management of the Valley Park was transferred from the City Council over to Devon Wildlife Trust. Ludwell Life and Exeter City Council are working together to create a new community orchard. This will turn what is currently a featureless field, low in habitat value, into a place for sitting and for picnics, provide a harvest for local people of fruit (the trees planted are all old Devon varieties), and also enriched habitat for wildlife. There will be a flat space to hold small community events too.

There is an old cherry orchard in the park, dating back to 1840, which contains some trees that are well over a hundred years old. These are being replaced, and a new cherry orchard was planted and is also being added to every year. The old hedges in the Valley also contain trees that are hundreds of years old, including pollarded Elms. These are being protected, and hedges that were removed in the 1920s are being reinstated. Wildflower meadows are being planted and hopefully this will continue. Ash tree die-back will be a devastating problem for Ludwell, as well as for the rest of the country, in the future. Vandalism and pollution are problems, but despite this, the Panny is still home to hundreds of creatures: kingfishers, dippers, egrets, ravens, buzzards, sparrowhawks, and maybe an otter. One of the objectives is to get people using the Ludwell Valley Park more – it is such a wonderful green space and we could all benefit from spending some more time there.

Scroll to top of pageHeavitree Stone And Heavitree Quarries

During the Permo-Triassic period, around 280 million years ago, the climate in Devon was like that of the present-day Sahara. Seasonal flash floods swept large quantities of sediment into the valleys and the plains fringing the deserts. As the stones within never had the chance to wear down, they remained angular and sharp. It is this mixture of stones and sediment, known as breccia, present in the Heavitree area, that was quarried and used for building in the Exeter area, where it was called Heavitree Stone.

A map showing the location of quarries in the Heavitree / Wonford area

Although Heavitree Stone had been in use for a long time, the first quarries opened at Heavitree, Wonford, Whipton and Exminster, around 1340, and continued operating until the mid-19th century. The first recorded use of Heavitree Stone was in Exeter’s Underground Passages in 1349. Cathedral records indicate a sudden increase of stone being brought in from Whipton - no less than 650 loads were conveyed in 1349-50. For some reason, the Cathedral was required to repair the City wall by the East Gate. It seems that this may have been because the Cathedral had decided to simplify its water supply (previously taken from St Sidwells well and carried around the city by conduit to Cathedral Close) by cutting through the East Gate, hence the repairs and material required.

The Underground Passages

Post-1350 and through the 1400s, there was a great flowering of masonry skills after the devastation of the Black Death, and a real pride in workmanship and in re-building of the city. The use of Heavitree Stone ashlar (large, square-cut blocks of stone) was connected with a big increase in the quality of building and was regarded as a real showpiece.

Heavitree Stone's heyday was in the 15th and 16th centuries. Churches dating from the period indicate that it was the preferred choice in Exeter. St Mary Steps is built from grand Heavitree Stone ashlar, as is St Stephen's, and the tower of St Martin's; Heavitree's St Clare's Chapel is a lovely example. Sadly, St Michael's Church is made from limestone, not Heavitree Stone, but perhaps it used to be. When it was rebuilt by the Victorians, part of the old church probably went to form the boundary wall between the two graveyards, which contains a whole mix of interesting materials: Heavitree Stone, red sandstone, volcanic blocks and medieval floor tiles.

A wall at Heavitree Parish Church

Another place in Exeter where we can see Heavitree Stone from the Middle Ages is in the old city walls. Although in places the Heavitree Stone is actually beneath the Roman volcanic stone, this does not mean that it is older, but is actually because the older wall is on top of the newer part; the ground would've been much higher on both sides, so when this was levelled, would've been underpinned with Heavitree Stone.

A section of the City wall

Moving away from Exeter there are some wonderful examples of the use of Heavitree Stone, in Alphington, Kenn, Kenton and Exminster churches, but in general its use peters out in favour of more local sources within a few miles.

Although Heavitree Stone is a high-quality material, it is prone to weathering. For this reason, there was something of a move away from its use from the 17th century onwards, but there are later examples, such as Wynards Almshouses and Chapel on Magdalen Street.

The chapel of Wynards Almshouses

Heavitree stone was used so ubiquitously through the City that its remnant walls act as a kind of red skeleton showing the shape of our City from 500-600 years ago. Today there are many lesser examples that can be still be seen in the form of low, basal courses that would have been beneath traditional cob or wooden structures.

Scroll to top of pageA Social History Of The Royal Devon And Exeter Hospital

This article contains portraits from a collection donated to the RD&E Hospital. Each one was produced either on appointment of the figure or brought with them when they came onto the board. The paintings acted as the PR tools of their day, and tell the history of the RD&E from a really interesting angle.

When the RD&E (Southernhay) site was put up for sale to private developers, the paintings were rescued with a view to reuniting them in the boardroom at the RD&E (Wonford). However, there was insufficient space therein, so a new boardroom was proposed.

Many, rightly or wrongly, took exception to this; the paintings had, after all, been in storage for many years.

They were gifted to the RAMM to be restored, and recently displayed at an exhibition there.

The RD&E Hospital was established in 1743 in Southernhay, Exeter, by Dean Alured Clarke. In the late 1600s / early 1700s, the idea of the great and the good coming together was very popular: the conception of public service.

The original RD&E Hospital, Southernhay, Exeter

Clarke (below) had trained in London and was acutely aware of the development of district hospitals at that time. When promoted to Dean of Winchester, the first thing he did was to gather the important people of the area around him and found Winchester Hospital. He then moved to Exeter; just a few records show how he went about his mission to build the Devon and Exeter Hospital. He came here in 1741 and got things moving, but unfortunately died a year later.

Dean Alured Clarke (founder of the RD&E Hospital)

Bishop Stephen Weston (below), Clarke’s boss, extolled the parish clergy and parishioners to donate money. This was raised by subscription, relatively small, but many of them; this gained pace as people recognised the hospital was to be a reality. The next stage was to secure the land.

Bishop Stephen Weston

John Tuckfield (below) was a local business-person, and later both alderman of, and MP for, the city. He was the president of the board. His portrait was painted by Thomas Hudson who produced three portraits in the collection; he was famed for his painting technique of textiles.

John Tuckfield

Ralph Allen (below) was born in Cornwall to a mining family. His mother was involved in the emerging postal service. At this time, many seams of copper were being discovered; those laying claim to them needed to register their ownership with an office in London. Unscrupulous people might intercept and change the name on the letter. Ralph recognised this and at 19 moved to Bath and became a postmaster. He rationalised the service in England and unified the whole system. He was the Bill Gates of his day, and made a huge fortune.

Once this wealth was in investments, he began opening stone quarries; the whole of Bath used this stone. These two careers made him a multi-millionaire. Having secured his place on earth, Ralph went about buying his stairway to heaven. In the painting, he is pointing to the deed that transfers part of his fortune to the hospital.

Ralph Allen

Having garnered everything, the board next went about attracting the best medical men.

John Patch Senior (below) is painted in the mode of lecturer. He is gesturing to learned text about the human hand; there is also a flayed arm in the painting. The portrait is remarkable, because at the time both the church and state were vehemently opposed to dissection of the human body.

John Patch Senior

Patch was the surgeon in Paris to James Edward Stuart (son of the deposed James of England, claimant to the English and Scottish thrones). The infant prince had been taken to France where James II had set up his court in waiting. Looking closely at the top right of the portrait, behind some crude over-painting, is a bookshelf with volumes on.

John Sheldon (below), surgeon at the RD&E, was a remarkable person. The Age of Enlightenment is embodied in some of his interests. He was somewhat bizarre. He kept the naked embalmed body of a 24-year-old woman next to his bed for thirty years. His widow gave the specimen to the RD&E.

The body was believed to have been his first love, who died of consumption when he was treating her in the final stages of illness. He also once ascended in a static balloon and was on course to travel the whole of the South Coast (but got off in Sunbury).

An interesting talk on John Sheldon, that's free to listen to, can be found here.

John Sheldon

The painting of Sheldon is very interesting because of the figure in the background. Around 1820-25, three royal academicians were involved in discussions about how Christ’s dead body would have looked on the cross. They were very interested in how the body would have ended up, and thought that the pose used by many artists was anatomically incorrect.

Until 1832, the Anatomy Act stated that the only bodies legally available for dissections were those of executed criminals. Therefore, casts of flayed cadavers were very important to medical schools and art galleries.

The three academicians approached a surgeon, and in 1801 he was asked to find a suitable subject. It just so happened that he knew a judge with an ‘open / shut case of murder’ coming up. James Legg, a Chelsea Pensioner probably suffering from dementia, challenged another Pensioner in his home to a duel, shooting him through the chest. He was hanged and afterward his body dissected, casts being made, pre- and post- dissection. From these casts, smaller versions were sculpted; one is the piece depicted in this portrait, another remains in the life drawing room at the Royal Academy.

As for the RD&E itself …

By 1974 it had out-grown the Southernhay site, and was moved to a tower block within the grounds of Wonford House. The new site is now known as RD&E (Wonford).

| The new RD&E (Wonford) |  |

|

|---|---|

| Artist's impression | Building work |

Initially, there were complaints from night-staff about the noise of gunfire from the nearby Wyvern Barracks, where the army shooting range was located.

Two people died falling from height at the hospital within a year of it opening, the first being a workman on the outside of the building, and the second a nine-year-old patient who fell down a service shaft.

In 1985, the building was the first major structure in the UK found to have concrete cancer (the alkali–silica reaction), which caused the concrete to expand and fail. It is thought that condensation from the kitchens was the primary cause.

The replacement buildings were built in several phases, the first phase being completed in 1992. This first phase included an ophthalmic unit which replaced the West of England Eye Infirmary, previously on its own site on Magdalen Street in the city centre.

Further building at the RD&E (Wonford)

The second phase was completed in 1996, followed by the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry opening in 2004, and a new maternity and gynaecology unit, known as the Centre for Women’s Health, opening at Wonford in 2007, with maternity moving from its Heavitree site in Gladstone Road.

The Heavitree site had existed for years as a place of healing, albeit under the banner of the Workhouse. It still exists, and operates a number of outpatient services.

The Southernhay site was sold to private developers in the early 2010s, and has since been converted to housing whilst retaining the external façade.

Scroll to top of pageCity of Exeter Lunatic Asylum, Digby - Part 1: 1890

Old minutes from Exeter City Council meetings (rescued from a skip) provide very interesting snapshots of Exeter life in the past.

The minutes from the Asylum Committee are particularly interesting; they give a glimpse into the institution at various points over the years. Not a comprehensive history of the Asylum, but rather a peek at various points in time (and, of course, seen through the subjective eyes of the Council Asylum Committee).

In the late 1800s, Heavitree wasn't yet part of Exeter, however the City sometimes took land to build facilities for which there was insufficient room in Exeter. One of these was the City of Exeter Lunatic Asylum. There was already a private mental hospital for the rich at St Thomas, replaced by the larger Wonford House (also in Heavitree parish) in 1869, but in 1880 the city decided to build its own municipal lunatic asylum, to treat the pauper lunatics of Exeter.

The land chosen was part of Digby Farm, within the old Heavitree parish. It was near the railway line, which would allow for building materials to be transported. In 1908, a station named ‘Clyst St Mary and Digby Halt’ was opened (350 metres from the current station).

OS Map dating from 1892-1908 showing the location of the City of Exeter Asylum, Digby

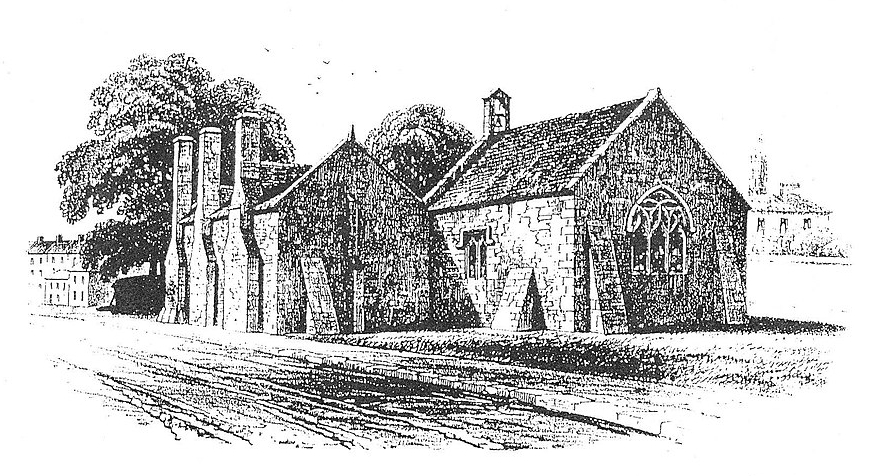

The Asylum was designed by Robert Stark Wilkinson. Exeter Memories describes the layout:

‘The building, of some 237 metres (777 ft) in length, was split into the more utilitarian north-western range containing the service, administration, and laundry rooms, along with accommodation for the laundry workers. The south-eastern range was a series of male and female ‘inmate’ areas separated by a recreation hall. In the centre of the range was a grand entrance into the main hall, as befits such a building. At one end of each range was a large tower, of differing design. There was also a farm for the Asylum, to the south-east of the main block, providing work for the male patients.’

Lithograph drawing of the Asylum

Early photograph of the Asylum

Photo amalgamation showing the position of the Asylum relative to current buildings.

Credit: Jerry Bird (Exeter Memories)

The first set of records dates from 1890, when the Asylum was still being equipped.

The accounts list purchases and services carried out: blankets, bedding, furniture, rugs, cutlery, carpeting, oil baize, brushes, oak posts and painting oils, sheets, trousers, armchairs, counterpanes, sheets, glass and earthenware, painting and writing, ironmongery, repairs to wire fences and ‘town dues on stone’.

The Council had to deal with a letter from W. Burrow, complaining that his tender for the supply of flour to the Asylum had not been accepted, despite it being the lowest. The Council informed him that:

‘Samples sent were made into bread before the Committee arrived at a decision, and that they were of the opinion that the small increase in the price of flour paid was more than compensated for by the superior quality.’

In 1890, the annual balance sheets showed that the Asylum loan, taken out in 1886, of £90,000 and a further £7,000, had been paid off by £7,381.

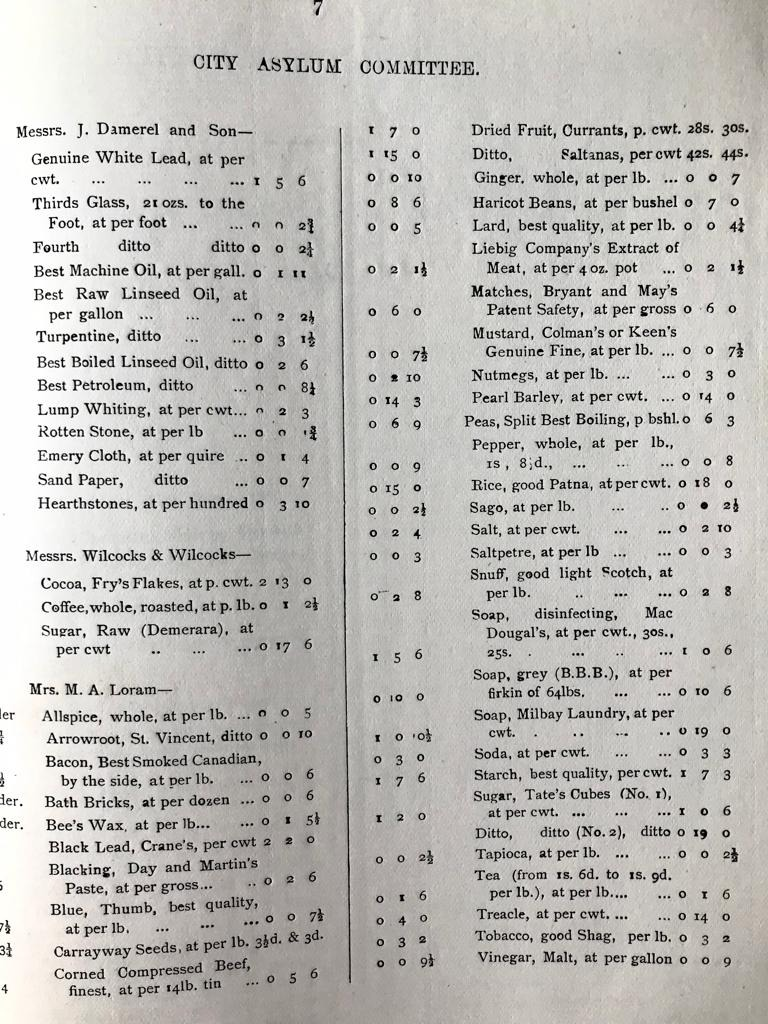

Sample from the minutes from the Asylum Committee

The City Asylum Committee met each month.

In January 1890, they were mainly discussing tenders for goods. The clothing purchased gives us an idea of what the patients would have been wearing:

’10 dozen men’s caps, 8 pieces of check shirting, pairs of flannel drawers, flannel vests, shawls, men’s stockings, 60 pairs of light cord trousers, 2 pieces of dress ticking, 20 dozen women’s stockings, 10 dozen flannel chemises, 600 yards of Wincey, 6 dozen pairs of stays, 6 pieces of striped skirting, 20 dozen women’s hats, 10 dozen pairs of braces, men’s and women’s boots and slippers.’

In March, there was discussion about setting aside wards for private patients, and also accommodating patients from London, Tiverton, Barnstaple and other Devon Unions. This seemed to worry the ‘Corporation of the Poor’.

A letter from their clerk demanded to know whether the weekly charge for lodging the City’s lunatics would be reduced to match the amount that would be charged for the ‘metropolitan lunatics’. The Committee replied, reassuring him that only the ‘better class of patients are to be received and that such patients can be maintained at a less expense than can acute and violent cases.’

Despite this, a compromise was suggested:

‘Being anxious to meet the views of the Corporation of the Poor, the Committee have offered to reduce the charge to 12s 10d per week, provided all the lunatics now at the Workhouse (which are chronic cases, the cost of whose maintenance is less than that of acute cases) are also sent to the Asylum.’

We find in April that the Corporation for the Poor refused to move these patients, deeming it ‘inexpedient’. The Asylum Committee dug their heels in accordingly and refused to reduce the charge per patient.

In December 1890, however, the Committee announced that they would reduce the charge for the Exeter patients from Lady Day (25th March) the following year.

The Commissioners in Lunacy made their annual inspection and it all sounded very positive:

‘The various day rooms and corridors present throughout a very bright aspect, and are made cheerful by the prints on the walls and the abundant supply of plants and ferns. The healthy appearance of the latter is perhaps due to the absence of gas, and the advantage in this respect which the Asylum has of being lighted by electricity.’

Great praise was given to Dr Rutherford and attention was drawn to the Medical Officer’s report:

‘… I have called attention to the great importance of early treatment of insanity; but I am afraid that until the public can be made to understand that insanity is simply one kind of brain disease, and that if treated early many varieties of it are very curable, the unfortunate patients will continue to be either retained at home or in workhouses until the curable stage of their mental disorder is past.’

Other observations from the Commissioners were:

‘A woman having sustained fracture of the spine, though for several months thereby paralysed, has recovered from that injury and was today running about a ward …’

‘6 men and 8 women were in bed today, some of them to allay excitement and not really ill. 4 males and 7 females are registered as being under medical restraint, and no one was under mechanical restraint or seclusion. There has been no resort to the former method of treatment, and but few patients have been subject to the latter – 8 men for an aggregate of 57 hours, and 1 woman once only for an hour and a half.’

‘The epileptics are 24, and the actively suicidal stated to be 12. All these sleep under continuous supervision at night, and for constant watch over those dangerous to themselves proper instructions in writing are issued to the staff. We, however, today saw a suicidal woman left alone in bed, in whose case the special instructions were not withdrawn.’

‘The provision of clothing for both sexes is good, and their general appearance in the better wards is satisfactory. Except in one ward, where there are certainly a very degraded and noisy class of patients, the inmates of the Asylum under certificates behaved well in our presence. Their excitement, we believe, was to some extent due to want of sufficient outdoor exercise. There was no turbulence on the male side. It is only fair to say that most of the excited and untidy women had contracted bad habits before their admission here.’

The Commissioners did seem concerned by the lack of exercise that patients were getting, and recommended that Exeter Council give permission to construct a boundary walk for daily use, particularly for ‘Those women who are unfit to be taken on the public roads.’

The diet was found to be satisfactory, except that they recommended that coffee be substituted for water at dinner, ‘Since beer is no longer given in many asylums … the other general beverage of the working class should be given to patients.’

Regarding work, they found that, ‘Looking to the returns of employment, the male patients induced are 46, the female patients 52, of the former 18 only on land, of latter 10 in the laundry, in the kitchen and offices, and 16 at needlework … 10 men and 16 women are chiefly employed as ward cleaners.’

Sample from the accounts of 1890 showing typical purchases for the Asylum

Accounts for the rest of 1890 were mostly concerned with spending and income. Items purchased give a good idea of what was being eaten: cheese, butter, eggs, cocoa, coffee, split peas, bacon, dried fruit, tea, caraway seeds, jam, haricot beans, lard, mustard, pearl barley, tapioca, treacle, pepper, sago, nutmegs, Liebig Company’s Extract of Meat, rice, ginger, corned compressed beef, best ox, heifer beef and best ewe, flour …

Non-edible items are also interesting: genuine white lead, machine oil, petroleum, lump whiting, rotten stone, hearthstones, bee’s wax, black lead, ‘blue thumb’, Bryant and May’s Safety Matches, good light Scotch snuff, soap (disinfecting), soap (grey), soap (Milbay Laundry), good shag tobacco, Englebert’s Lubricant, rental of telephone, allowance to patients on trial/working, wines, spirits and beer …

The Superintendent of the Fire Brigade, a Mr Pett, came and examined the building and its means for the extinction of fire. He recommended ways of using water from the City Water Works and the Asylum Well and Reservoir; he also found the Asylum fire hydrants completely useless, suggested the purchase of one 30ft telescopic fire escape, and said that the male attendants should be instructed in the use of fire appliances, etc. He finished by suggesting that the fire hose should not be used for ‘flushing drains, etc.’

Scroll to top of pageHeavitree And Infectious Diseases

The Government-imposed national lockdown of Spring 2020, in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, was a challenging time for everyone; it was certainly the first major disruption to everyday life experienced since World War II. Every person will have been affected differently by the restrictions: for some it will have been the longest period spent in Heavitree without leaving the area; some may have felt increasingly isolated and lonely, desperate for a change of scene, their wellbeing going downhill as time wore on; some may have used the time to do the jobs they never seemed to get around to; others may have taken up a new hobby, or discovered new things such as walks, wildlife, or historical facts; a few may even have paused to wonder what Heavitree might have been like in previous times of infectious diseases, epidemics, or pandemics.

Leprosy

Leprosy would have been a regular feature of life in Exeter and the rest of the country by 1050. The disease is a long-term bacterial infection that leads to damage of nerves, skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract, and deformity or loss of limbs.

The social perception of Leprosy in medieval communities was generally one of fear, and people infected with the disease were thought to be unclean, untrustworthy, and morally corrupt. Segregation from mainstream society was common, and people with Leprosy were often required to wear clothing that identified them as such or carry a bell announcing their presence.

Map from 1805 showing Magdalen Hospital (Image courtesy of Exeter Memories)

Leper hospitals were situated on the outskirts of towns. The clue to where Exeter’s main leper hospital (there were also many smaller ones) was located is in the name ‘Magdalen Road’. Many leper houses were dedicated to Mary Magdalen, probably because of her supposed brother Lazarus (described in the Bible as, ‘a beggar full of sores’); a shortened form of his name (Lazar) came to mean Leprosy. Others claim it was because of the association between her and sexual excess and prostitution, which were incorrectly associated with Leprosy.

According to ‘Exeter Memories’:

‘The Magdalen Hospital was situated in Bull Meadow and consisted of a quadrangle with a chapel on one side and small buildings to house the inmates on the other three. Inmates were confined to the hospital and could be punished with a stint in the stocks if found wandering in the city.’

For a while, lepers were permitted to collect alms door to door and claim tolls on corn, but after this was forbidden, they were reliant on charity and bequests from Exeter residents.

As Leprosy began to disappear (there were still cases being recorded in 1530), the hospital was used to house the poor; it was demolished in the middle of the 19th century. Only the name ‘Magdalen Road’ remains, reminding us of these poor people’s fate.

The ‘Historic England’ website reveals another lasting effect:

“The impact of Leprosy lived on - it had brought about an institutional response to disability in the form of buildings and methods of care which would strongly influence future generations.”

The Black Death

Like the rest of the country, Exeter was devastated by the Black Death, which we think (like COVID-19) came from China; it lost 1900 out of 3000 of its inhabitants.

The Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio wrote:

“At the beginning of the malady, certain swellings, either on the groin or under the armpits … waxed to the bigness of a common apple, others to the size of an egg, some more and some less, and these the vulgar named plague-boils. Blood and pus seeped out of these strange swellings, which were followed by a host of other unpleasant symptoms — fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhoea, terrible aches and pains — and then, in short order, death.”

Image depicting individuals suffering from the Black Death

The Black Death, which was initially spread by rats, was very infectious and could be caught from respiration or from contact with an infected person. People who were perfectly healthy when they went to bed at night could be dead by morning. At the time, nobody knew how it was spread.

One doctor from the time said:

“Instantaneous death occurs when the aerial spirit escaping from the eyes of the sick man strikes the healthy person standing near and looking at the sick.”

Most people believed that the Black Death was God showing his anger at man – almost clearing the earth with a second great flood. It must have been terrifying. People sometimes even abandoned their sick or dying loved ones, because they were so afraid of catching it.

Ian Mortimer’s novel ‘The Outcasts of Time’ describes two brothers walking from Honiton to St Sidwells, Exeter, via Heavitree, at the time of the Black Death of 1348. The scene Mortimer paints shows us how times must have felt almost apocalyptic to people who lived in the village of Heavitree and the nearest city, Exeter – houses with their shutters closed, corpses everywhere, mass graves being dug:

“Death is all around us. I see it in the windows whose shutters remain open when dusk comes, and in the shutters that remain closed of a morning. I see it also in the unguided progress of a boat that floats down a river with the occupant slumped over the side, bumping into banks and quays. … In a few areas the crops lie unharvested, crumpled, and black, but in most places the disease struck after the grain was taken in. Less reassuringly, the fields are empty, devoid of workers. At dusk we are a mile from Exeter. More travellers approach – dark characters in ones and twos, shielding their faces with their hoods. A couple more carts come towards us. All these people are like shadows fleeing the city: wraiths of traders and merchants. But none of them are what you would call the naked poor, travelling on foot. The impoverished are staying behind – either to loot the houses of the rich or because they have nowhere else to go.”

This flight from the cities did not save people from the Black Death (although it did a good job of spreading it!), and farm animals could also be infected and die from it. It is interesting to note that during the current pandemic, moving from the city to the countryside and working remotely has become more popular, according to estate agents.

It was widely believed that the Black death was God showing his anger toward man

In Heavitree, the Black Death caused the death of two, if not three, vicars. Henry de Chippenham, who had held the post for less than a year, was succeeded early in 1349 by Walter Bers, who was himself followed by Adam de Kellesye. The date of institution of his successor, John Lisle, is not recorded, which suggests that Kellesye also may have died during the period of disorganisation caused by the Black Death. The higher death rate among the clergy may have left people doubting the church as an institution, especially as it was the church itself that had given the cause of the Black Death to be the impropriety of the behaviour of men. These holy men had been seen as God’s envoys on earth but were not immune to his punishment. This change in perspective would have sown seeds for The Reformation in years to come.

Heavitree and Exeter would have felt many other effects of the Black Death, for many years after – most directly via the huge shortage of labour brought about by such a reduction in workforce. This eventually led to wage increases, the abolition of serfdom, and the development of family surnames for the lower classes. Like today, the arts and culture suffered badly, for example a shortage of labour led to a halt in building Exeter Cathedral.

The Black Death never really went away completely returning to Devon several times over the next 300 years. Fatal pestilences are recorded to have happened in Exeter in 1378, 1398, 1438, 1479, 1503, 1546, 1569, 1590, 1603, 1624 and in 1625, more than 2000 people died. Although some of the suggestions for causes of, and cures for, COVID-19 have been extreme (5G and injecting bleach, anyone?), in the 17th century, people still mostly believed that the Black Death was a punishment from God; they tried everything from fasting to eating frogs’ legs, purchasing powdered ‘unicorn horn’, or rubbing a recently killed pigeon to buboes!

Sweating Sickness

The mysterious Sweating Sickness is thought to have spread from Henry VII's army after it landed at Milford Haven in Wales on 7th August 1485.

One commentator at the time described it as:

“A newe Kynde of sickness came through the whole region, which was so sore, so peynfull, and sharp, that the lyke was never harde of to any mannes rememberance before that tyme."

Image depicting an individual suffering from Sweating Sickness

Whereas other epidemics were typically urban and long-lasting, cases of Sweating Sickness spiked and receded very quickly, and heavily affected rural populations. 443 people died of the disease in Tiverton – a huge chunk of the town’s population. There is no record of its effect on Heavitree or Exeter, but it is likely to have been very fatal. Giddiness, headache and severe pains in the neck, shoulders and limbs occurred, followed by an intense sense of heat, headaches and delirium, a rapid pulse and intense thirst. Heart palpitations and chest pains were also common. Patients then had a strong urge to sleep, with many claiming that if the patient did doze off, they would seldom wake up again. It was particularly noteworthy for its speed – patients were often dead within three to twelve hours. Like COVID-19, people could catch it more than once.

Smallpox

Europe was struck by its first Smallpox epidemic in 1614; the frequency of epidemics rose during the century. After 1666, it replaced the Black Death as the most feared disease. By the early 18th century, Smallpox was a major cause of death in the British Isles.

The city was certainly subject to sudden outbreaks of the disease:

“The small-pox was very prevalent at Exeter in 1777, when out of 1850 who had it in the natural way, 285, rather more than one in seven, died of that fatal distemper.” (Magna Britannia, Vol 6)

‘Exeter Memories’ tells us that in 1871 there were plans to build a Smallpox Hospital in Polsloe Road, Heavitree, which did not impress the locals.

It does seem likely that, unlike in the North of the country, Smallpox was not endemic in the population of the South-West. This is thought to be because local parishes were much better at containing and isolating the virus. Those infected would often be sent to ‘pest-houses’, away from the rest of the population. Not many children would have had Smallpox, which would have meant fewer deaths, but a huge vulnerability when visitors arrived, or for anyone from Heavitree travelling to an area where Smallpox was rife.

Image depicting an individual suffering from Smallpox

There was indeed much to fear from the infection. Three to four days after developing a fever, the characteristic pus-filled pocks would appear. They were extremely painful and would burst easily, giving off a foul odour.

The historian Thomas Macaulay describes it vividly:

“Always present, filling the churchyard with corpses, tormenting with constant fear all whom it had not yet stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the betrothed maiden objects of horror to the lover.”

During the 20th century, Smallpox was responsible for 300-400 million deaths, and in 1967 the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that around 15 million people had the disease and 2 million died in that year.

Fortunately, after various vaccination campaigns during the 19th and 20th centuries, Smallpox was considered to be globally eradicated in 1979 by the WHO.

Cholera

A riot at a Cholera burial in the Southernhay or Trinity burial yard (Image courtesy of Exeter Memories)

One pandemic that almost certainly would have contributed to the growth of Heavitree, was the Cholera outbreak of 1832. Officials were not sure how Cholera spread, and so many rules were put in place for disposal of bodies, clothes, and bedding, isolating patients, etc. The city spent a fortune supplying everybody with a ‘flannel belt’, thought to prevent the Cholera by keeping one’s stomach warm! People were frightened because they didn’t know the cause of the disease, which was later found to be spread via water. Paranoia, drunkenness, and lawlessness were rife, and just like in today’s pandemic, there were some who believed that the whole epidemic was a conspiracy. The city carefully recorded the number of cases, as we do today.

Heavitree seemed clean in comparison to the squalid conditions in the West Quarter

Since the outbreak was happening in the city (at its worst in the poor, crowded West Quarter), many people believed that quality of air had something to do with it, and Heavitree was thought of as a healthy place to live. It was marketed for its clean air, which attracted rich and poor alike. In 1801 the population was still just 833, but by 1901 this had risen sharply to 7529. The Cholera epidemic changed much about the city but also contributed towards Heavitree becoming a much more populous area.

Syphilis

Syphilis was the first disease to be widely recognized as a sexually transmitted disease, and was taken as indicative of the moral state of the people in which it was found.

“The disease started with genital ulcers, then progressed to a fever, general rash, and joint and muscle pains, then weeks or months later were followed by large, painful and foul-smelling abscesses and sores, or pocks, all over the body. Muscles and bones became painful, especially at night. The sores became ulcers that could eat into bones and destroy the nose, lips, and eyes. They often extended into the mouth and throat, and sometimes early death occurred. It appears from descriptions by scholars, and from woodcut drawings at the time, that the disease was much more severe than the Syphilis of today, with a higher and more rapid mortality and was more easily spread, possibly because it was a new disease, and the population had no immunity against it.” (John Frith)

Image depicting individuals suffering from Syphilis

We don’t know how many people suffered from Syphilis in Heavitree or Exeter, but it certainly would have been present in the population. Indeed, in August 2020 it was reported that there has been a 400% increase in Syphilis diagnosis in Exeter in the past twelve months! Luckily, we have antibiotics these days so won’t see anyone with a metal nose, or being subjected to blood-letting, swallowing mercury or baths in wine (the latter doesn’t sound so bad!).

Measles

In 1907, Measles, an airborne and extremely contagious virus, was mentioned in Heavitree School log:

“18th July 1907: cases of Measles increasing - school closed for the Summer Holidays two weeks earlier than fixed.”

Image depicting an individual suffering from Measles

Like COVID-19, Measles is usually spread through droplets in the air created when someone coughs or sneezes, and again like COVID-19 one could infect others before showing any symptoms oneself. Between roughly 1855 and 2005, Measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide, and 7 to 8 million children worldwide are thought to have died from Measles each year before the vaccine was introduced. In 1968 this vaccine almost eradicated Measles, along with Polio, Diphtheria, Tetanus, Whooping Cough, Mumps, and Rubella (although cases are now growing again as fewer people are vaccinated). Almost all children living in Heavitree up until the vaccine was introduced would expect to get Measles at some point, and it was one of the leading causes of death for under fives.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by a type of bacterium called Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. It is spread when a person with active TB disease in their lungs coughs or sneezes and someone else inhales the expelled droplets containing TB bacteria. Mortality from Tuberculosis was colossal: 1 of every 4 deaths recorded in parish registries from England at the end of the 18th century was attributed to the disease.

The Sanatorium, Whipton Isolation Hospital (Image courtesy of Exeter Memories)

In the same way that Measles devastated many families, bacterial TB would have affected young and old in Heavitree. Many Heavitree residents will remember the TB Sanatorium at Whipton Isolation Hospital and Honeylands Sanatorium. The latter was donated by the Wills family (ironically made rich by the tobacco industry) for children suffering from TB and other infectious illnesses like Diphtheria and Scarlet Fever. At this time, Heavitree would have had its own separate hospitals, and of course, Whipton fell within the Heavitree boundary.

Honeylands House

Some former patients shared their memories on the 'Exeter Memories' page. The sheer number of people, often children, who spent long periods in isolation, suffering from one of these horrible infectious diseases, is very striking: